Here are just a few reasons why you might want to read Beowulf. First, it is a famous example of literature from the Early Middle Ages. Second, it represents English-language literature in its infancy. Third, it has had impacted modern literature since its rediscovery.

Here are just a few reasons why you might want to read Beowulf. First, it is a famous example of literature from the Early Middle Ages. Second, it represents English-language literature in its infancy. Third, it has had impacted modern literature since its rediscovery.

The Early Middle Ages, although politically fractured and certainly with a lower standard of living than the Later Roman Empire or the High Middle Ages, are a period of great creativity and transformation within western Europe, as the post-Roman world resettles itself into something new. Beowulf is, in many ways, indicative of the Early Middle Ages. Culturally, the Early Middle Ages see the introduction of literacy and Christianity to more and more ‘barbarians’—the English, Irish, Scots, Dutch, various continental Germanic peoples, Danes, and more. As a poem about the pagan past being told from a Christian perspective, Beowulf encapsulates the early medieval world, not simply by showing us aspects of Anglo-Saxon society (the beerhall with the lord bestowing gifts upon his thegns—the world of Sutton Hoo), but of European society more broadly (the transformation of barbarian pagans into literate Christians).

Beowulf is one of the earliest long-form English poems. It shows, in a certain way, the foundations of English literature. This is a lofty claim; Beowulf certainly exerted no direct influence on Chaucer, who certainly had closer English poets as well as French and Latin literature to hand. Nonetheless, Beowulf was written in the English vernacular, composed from the stuff of the oral legends that existed as part of the cultural inheritance the English brought with them from the Continent. Its intrinsic interest, then, is that it is a so-called ‘primary’ epic, such as Gilgamesh, the Homeric epics, and The Song of Roland, as opposed to Apollonius of Rhodes, Virgil, Dante, or Ariosto. It depicts a pre-literate, warrior society, yet is itself cast in a beautiful, lyric form. Beowulf carries with it not just daring adventure and heroism, but also the hope of heaven and high ideals of loyalty and honour. These are ideals that are known to capture the hearts and minds of most people. Reading Beowulf shows us English poetry when England was barely English.

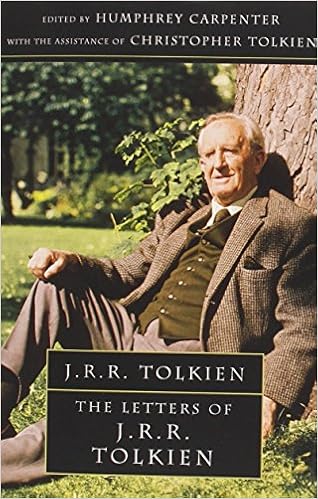

Finally, Beowulf has a strong influence on modern literature and art. Like most, if not all, early medieval vernacular literature, it lay dormant for many years. But nationalism, romanticism, and the rise of vernacular philology in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant that this Old English epic has found new life, being ushered back into the canon of English-language classics. Immediately, of course, J. R. R. Tolkien, Oxford’s first Professor of Anglo-Saxon and critic of Beowulf comes to mind—especially since the publication of his translation with notes in 2014. It is widely known that Tolkien was influenced by Beowulf in crafting his fantasies, and The Hobbit in particular. From my own experience, many young people have been ushered into classic literature through the twofold gateway of Tolkien and Lewis. Beowulf also inspired the later portions of Eaters of the Dead (filmed as 1999’s The 13th Warrior) when Michael Crichton takes the story beyond Ibn Fadlan’s surviving narrative.

Furthermore, modern adaptations have made Beowulf a known entity, but—like the famous Victorian trio of horror stories, Frankenstein, Dracula, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—very little read. It has been unfaithfully adapted multiple times for the cinema, as well as a more faithful animated version with the voice talents of Derek Jacobi and Joseph Fiennes. In print, John Gardner has given us Grendel, telling the tale from the perspective of the monster, and Gareth Hinds produced a vivid and captivating graphic novel. One of my favourite adaptations of Beowulf is the stilt play! There has also been an anthology of short fiction about the character inspired by the epic.

So, if you take C S Lewis’s advice and read an old book after every new book, why not pick up Beowulf next time? I’ve read and recommend the translations of Liuzza, Crossley-Holland, and Tolkien, but I expect Heaney’s is more than worth your time.