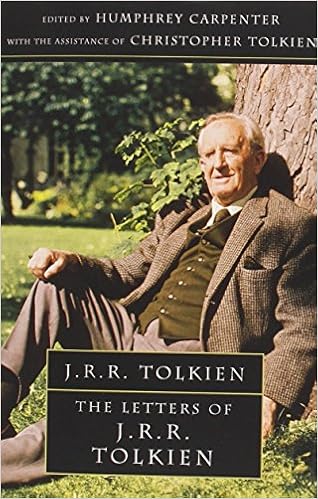

In a note to letter 212 in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, the master of fantasy writes:

In a note to letter 212 in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, the master of fantasy writes:

In narrative, as soon as the matter becomes ‘storial’ and not mythical, being in fact human literature, the centre of interest must shift to Men (and their relations with Elves or other creatures). We cannot write stories about Elves, whom we do not know inwardly; and if we try we simply turn Elves into men. (p. 285, second note)

This footnote caught my eye. Preliminaries are: Hobbits are men. Tolkien says as much in his letters, that Hobbits are part of the world of Men, not of Elves or of Dwarves. They a particular culture and breed of person who is, inwardly, human. This is important because the success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings lies in their being told from a Hobbit’s-eye view. You start small, local, parochial, and expand into a much bigger, broader, badder world, hopefully changing for the better along the way.

Second preliminary is that here we see that Tolkien is well aware of the psychological aspect of the novel. In his famous essay ‘On Fairy Stories’, Prof. Tolkien is keen to point out that the main point of a story — fairy story, short story, novel — is not the exploration of the human psyche but the telling of a story; this is made as a genre distinction agains the more psychological mode of storytelling found on the stage, as well as the at times purely psychological world of poetry. Of course, the stage used to be filled with naught but poetry. (Something T. S. Eliot tried restoring with Murder in the Cathedral.)

Preliminaries aside, as a reader of fantasy and science fiction and occasional dabbler into world building (or ‘sub-creation’ in Tolkien’s terms), this is an important point that could be forgotten. When you read Tolkien’s descriptions of who Elves are, what their function in the Creator’s world is, what their nature/substance is, what little is utterable about their culture and society, it is clear that they are not human beings. They are Elvish beings.

This means that, besides immortality and a longing for a world where time stands still, alongside a capacity for sub-creative art and linguistic generation, Elves are psychologically distinct from humans. Their ways are not our ways. Their thoughts are not our thoughts. Their reasoning may be different from ours. Certainly their emotions are. Their longevity also means that they have an entirely different approach to memory, I have no doubt.

Tolkien is aware of the world he has made, as well as the limitations of the authorial act.

When I think on the Dragonlance novel Dragons of Autumn Twilight that I read aeons ago, it strikes me that the half-elven character was little more than a man with pointed ears and elf-skills. That is — his psychology was entirely human. This is no fault of the authors. I have a feeling it would take extraordinary dexterity that few, if any, authors have to be able to render an entirely alien psychology.

And if one were to succeed, I think the story would become much less accessible to the reader.

Here we see, yet again, the wisdom and care of Tolkien not just in creating his world but in writing his novels.